Stay updated on what’s breaking in higher education with SmartBrief for the Higher Ed Leader.

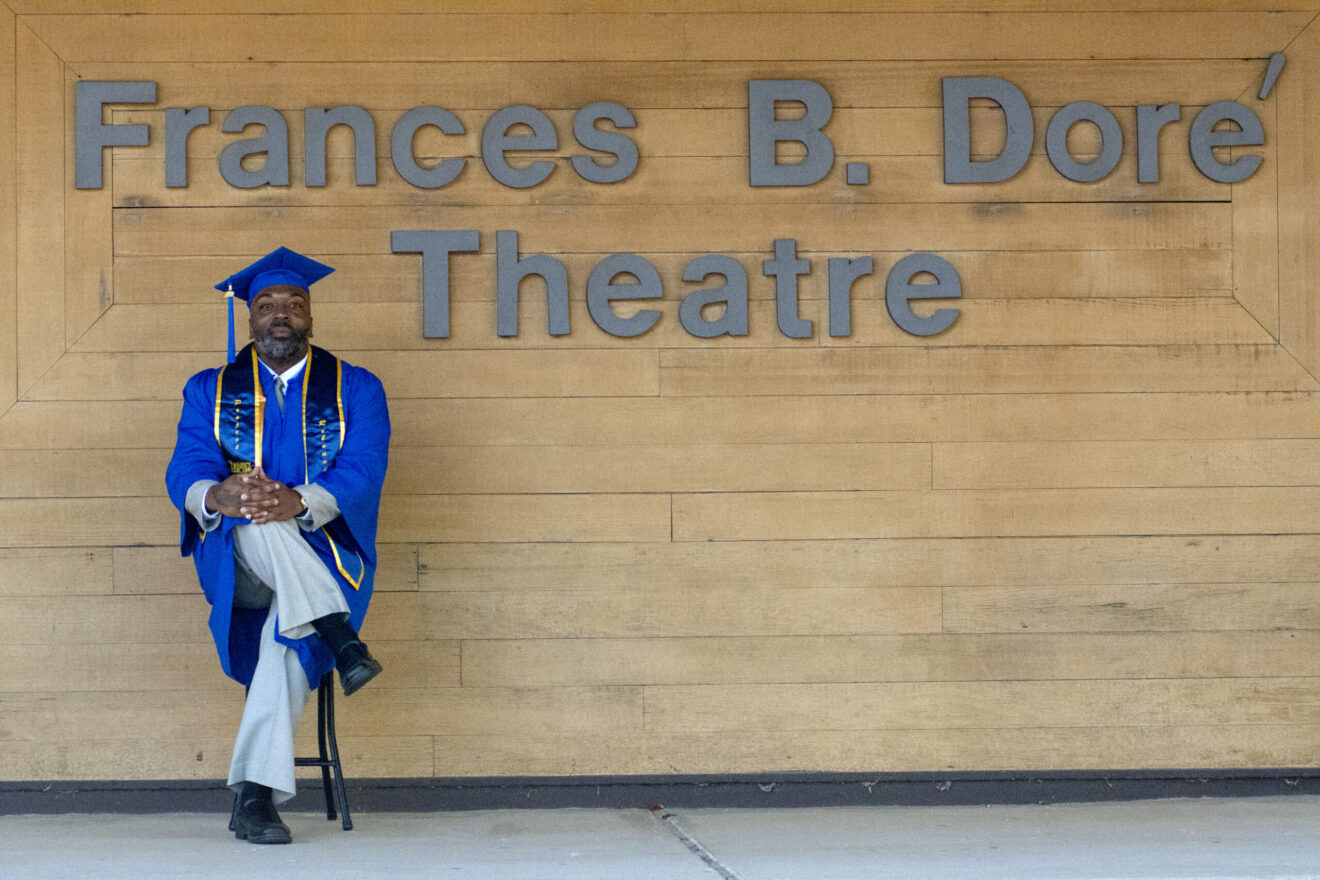

It was a glorious southern California morning. The December sun sparkled in the winter sky, and there was a slight chill in the air. John Hunter hired professional photographer and friend Raymond Edwards to help him with graduation photos at the California State University, Bakersfield, campus. It had to be just right. “I want to make my family proud, my community proud, people of color proud,” he says.

Just two years earlier — December 2018 — he had been released from prison.

“I’m surprised I’m still alive,” he says with a chuckle, his smile brightening his face.

At 6’1” with a powerful athlete’s carriage, he’s friendly and easygoing with a keen mind sharpened by experience and study. In his graduation suit and tie, he exudes confidence.

The man who served 10 years for assault has been erased by a budding playwright who writes poetry and published a book about Black male culture.

When there’s nothing else to do but get in trouble

Hunter was born in Sacramento, Calif., the youngest of three children; he has two older sisters. His father was in the military so the family moved a lot. When Hunter was 10, the family settled in Lompoc, a small town on the central coast of California. It was here that Hunter’s troubles began.

“I moved to this little town,” he says. “It wasn’t big enough to hold me.”

Hunter was a star athlete and straight-A student in his younger days, but his high school’s open-campus policy proved challenging for him, and skipping class and football and basketball practices became routine. Life at home became difficult.

“My family life was not all put together, and if your family life is not put together, you don’t really care much about anything else,” he explains. “So once I got kicked off the football and basketball teams, [there] was really nothing for me to do other than get in trouble.”

Hunter cycled through nine high schools before finally ending up in youth prison.

His troubles continued into his adulthood, culminating in a 15-year prison sentence in 2009 for assault with a deadly weapon. Thatprison stint may have saved his life, because it introduced him to Project Rebound.

The rebound begins

The day-to-day tedium of prison life led Hunter to seek out college coursework.

“You have to pick up a book; you have to do something with your time,” he says.

The first class he took was psychology. The remote, independent study format proved difficult, though, and he failed the course. When he transferred to a different prison, he was able to take classes in person. “And that’s when I excelled. I took the same psychology class over. Aced it,” he says with a grin.

Several classes later, Hunter had earned his associate degree and decided to pursue a bachelor’s degree. It was then that he met Michael Dotson, the coordinator for Project Rebound at California State University, Bakersfield. The initiative helps formerly incarcerated people attain their college degree. Dotson was promoting the program to inmates.

Project Rebound was founded in 1967 by John Irwin, a former felon who served five years in a California prison for armed robbery. While in prison, Irwin began taking college courses and, upon his release, continued his education at University of California at Los Angeles. After earning his Ph.D., he became a professor of sociology and criminology at San Francisco State University. Irwin created Project Rebound to matriculate people directly into San Francisco State University upon their release from prison. It is now a department at 14 institutions in the California State University system.

“The rest was really history for me,” Hunter says. “I dove in head first with it.”

With Dotson guiding him, Hunter began the long process of applying for admission and financial aid. He set up his parole program for California State University, Bakersfield, and chose theater as his major. Three weeks after his Christmas Day release from prison, he began classes. Hunter settled quickly into campus life — attending classes, doing schoolwork and acclimating himself into the theater program. He credits Project Rebound and its staff — Dotson in particular — for helping him navigate the system.

“Project Rebound is here basically to hold your hand and walk you through every step that you need. It’s like an ‘each one teach one’ program,” he explains. “And Michael Dotson’s door is always open. So if you just want to just go in there and say, ‘Hey man, I’m in class; I don’t know what’s going on,’ he’ll assist you. He’ll help you.”

Hands-on support is key to these students’ success, Dotson says. He and his team work closely with the students: while they’re incarcerated, to get them prepared and admitted, and when they’re released, to help them stay on track for their degrees.

The process starts when we meet them, Dotson says. The first step is a conversation to see if the inmate is eligible for entry to a participating institution. If they are not yet eligible, Project Rebound refers them to a junior college to begin their studies and sticks with them to see where they need support. “We don’t just send them over there and dump them,” he says.

Project Rebound has a 14-member support team, plus a five-member student support mentor group. The latter is composed of students involved with the program and are assigned to assist the incoming participants. Project Rebound also offers tutoring services, food and housing assistance, mental health support, a virtual community, and career guidance and internship placement. Dotson admits this type of end-to-end support is challenging but necessary for the students’ success.

“When you get out of prison and you head here, it’s not what you imagine. Now you have to sit down; someone has to help you,” says Dotson. “That’s why I built all these little programs in this thing — to make it work for them. It’s really difficult, but you need someone who has passionate compassion.”

Moving forward

It’s working. Project Rebound at California State University, Bakersfield, launched in 2016 and, to date, has graduated 12 students, with another 48 in progress, Dotson says. One graduate has been accepted into the master’s program in social work at the University of Montana. Another is the executive director of a sober living group. Hunter is writing plays and pitching ideas to Netflix and small theaters. No California State University, Bakersfield, students have returned to prison, Dotson says.

Project Rebound helps formerly incarcerated students develop a sense of confidence that motivates them and allows them to see new purpose and stay on course for rebuilding their lives. Hunter and cohort have become an inspiration for people still in prison. “A lot of guys who were still in prison would call me and say, ‘We’re so proud of you. Everybody in prison’s talking about you.’ It kept me going,” he says.

“They’re rising, they’re rising,” Dotson says. “They’re hungry for this knowledge, and they’re on it. That guy always had it in him and didn’t know it. We just had to help [him] get there.”

Kanoe Namahoe is the director of content for SmartBrief Education and Business Services. You can reach her at [email protected].

Sign up for SmartBrief for the Higher Ed Leader to get news like this in your inbox, or check out all of SmartBrief’s education newsletters, covering career and technical education, educational leadership, math education and more.