Sign up for our daily edtech news briefing today, free.

As the program director for history at Excelsior College — a fully online college that primarily serves adult learners — I have a particular interest in engaging experiences that incorporate social-emotional learning and help students develop historical empathy. The aim is for them to not just understand events, but the perspectives of those who lived through them and made the decisions that shaped the past and the present.

One common way history teachers do that is through role-playing exercises, but adults often resist that approach. Having students take on personas through writing in the voice of a journalist of a time period, for example, or staging debates can great ways to get adult students to approach the past with nuance and consider the conditions people faced at particular historical moments.

Perhaps one of the most engaging ways to look at history from specific perspectives, however, is through simulations. In our class HIS350: World War I, we use a series of simulations — we often refer to them as “games” because they are so engrossing — that ask students to step into the shoes of historical figures and make a series of decisions as they move through real historical events.

While the goal of our simulations is to encourage the development of historical empathy, the underlying principles should translate well to any subject in which students are challenged to see something from a different point of view — a critical skill for career readiness. Here’s how our simulations work:

The simulations

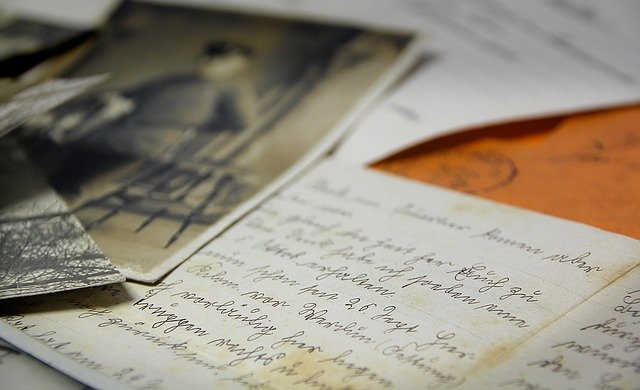

We developed our simulations with Dr. John Riley, subject matter expert in history and an avid game-player and another partner called Muzzy Lane, which provided the authoring platform and supported us in creating the actual simulations. The simulations are text-based but conversational, and incorporate imagery from the era throughout.

In the first experience, “The July Crisis: Be Kaiser Wilhelm” students take on the role of Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany before the outbreak of World War I. They have conversations with military advisors, British diplomats, and Czar Nicholas of Russia who also happens to be the Kaiser’s “Cousin Nicky.” Along the way, the students may make different missteps that cost them the support of their people or the empire’s money, until they reach an endpoint.

In the next simulation, “The True Cost of War: Be the General,” students simulate the role of a general in the trenches of the Western Front. They have to figure out how to gather intelligence before launching an attack: Do they want to use a military plane, a balloon, or stage a covert nighttime raid? They must also grapple with whether to use poison gas.

In the third simulation, “Making the World Safe for Democracy: Be President Wilson,” the students consider the lead up to America’s participation in the war through Woodrow Wilson’s eyes. This one is a little different than the other two in that there is only one outcome and the students know that going in. This simulation always ends with students going to Congress to request a declaration of war. Along the way, the students must gain the support of the people and Congress so that request goes smoothly and the country is prepared to go to war. They speak with military personnel to decide if they should institute a draft, talk with a suffragist about addressing democracy at home before fighting for democracy abroad, negotiate with a labor leader to prevent strikes, and make decisions about the use of propaganda and censorship.

The crux of the class

Students are not graded on the outcome of their simulations. There are no right or wrong answers because the point is experiential. Instead, students receive a 100% if they complete the simulations during the week it’s assigned.

While the simulations only account for about 10% of students’ final grade, they are the crux of the course’s organization and the jumping-off point for further critical thinking. Right after the simulation, students engage in class discussion to unpack it. They look at primary sources and their textbooks to put it into context and discuss how these decision-makers were constrained by their circumstances or the information they had at the time. During the week students often go back and try the simulation again two or three times to see how things shake out differently when their decisions change. Finally, at the end of the course, they complete a research paper on a topic that is related to one of the three simulations.

Why it works

The simulations are fantastic teaching tools because students choose to play them through multiple times, spending 45 minutes to an hour each time on simulations that could be completed within 15 minutes if they were just checking boxes.

These simulations work particularly well in the discipline of history because they put students into the moment in a way that is difficult to do just by reading. One of the concepts we reinforce in Excelsior’s history program is contingency, which is the idea that history did not have to unfold the way it did, nothing was predetermined. Everything is a product of its context, and things could have turned out differently with even slightly different decisions along the way.

We’re all prone to presentism, but these simulations help students break out of that mental framework so they can judge the past on its own merits instead of through a contemporary mindset. The decision about using poison gas, for example, may be an easy “no” today because of what we know about its effects, but for a general trying to break the stalemate in a brutal war where it was used by all major combatants, the cost-benefit analysis may look very different.

Many students even come out of the class with a bit more humility. They’ll often say they went into the first game thinking they could make all the right decisions and avoid the outbreak of World War I. After they play it through two or three times, they realize there aren’t any “winning solutions” that avoid the war entirely. .

Another source of healthy humility in the simulations is the mistakes students can and will make. One of the conditions that constrained decision-makers in the lead up to the war was the tangle of open and secret alliances. Students will often discover in the first simulation that they accidentally revealed secret information to the wrong diplomat, compromising their position. ,.

When you hear a student say, “You know, it was kind of humbling to realize that I was falling into that trap myself and that I didn’t have all the answers even with the benefit of hindsight,” you can be confident they’re beginning to understand historic decisions within the context that shaped them. Ultimately, they are developing the social-emotional skills needed for advancement in their education and their career.

Mary Berkery, PhD, is the program director of history at Excelsior College, where she uses simulation authoring platform Muzzy Lane. She can be reached at [email protected].

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Like this article? Sign up for our Edtech news briefing to get news like this in your inbox, or check out all of SmartBrief’s education newsletters, covering career and technical education, educational leadership, math education and more.

More from SmartBrief Education:

- Adjusting lab learning in a post-pandemic classroom

- Distance learning while respecting students’ home lives

- 8 ways to make vocabulary instruction more effective