Education psychologist Michele Borba was conducting a focus group on mental health with 12 students at a middle school in San Diego, Calif., asking them questions about their experiences with stress and anxiety. During the discussion, Borba noticed one student kept looking at the table behind him, where a jigsaw puzzle lay unfinished, with pieces missing. Today’s young people are like that puzzle, he told her – they’re missing the “pieces” of the puzzle to understand how to navigate life and it’s causing them enormous stress.

“How to be good people, how to solve a problem, how to get along with others,” he said. “The problem is we’re all being raised to be products and test scores by our parents that we can’t figure out how to do the rest of it and that’s why we’re struggling.”

It was a moment of clarity, Borba said during her morning keynote presentation Sunday at the 2023 ASCD Annual Conference.

“This generation of kids is like carefully wrapped packages of gifts with missing some pieces inside,” she said. “It’s not that we’re not trying. But we’re also raising our children in a different culture. The kids are the same; they’ve got the same needs but culture always matters. We’re looking at a more uncertain, unpredictable, fast-paced, accelerated world.”

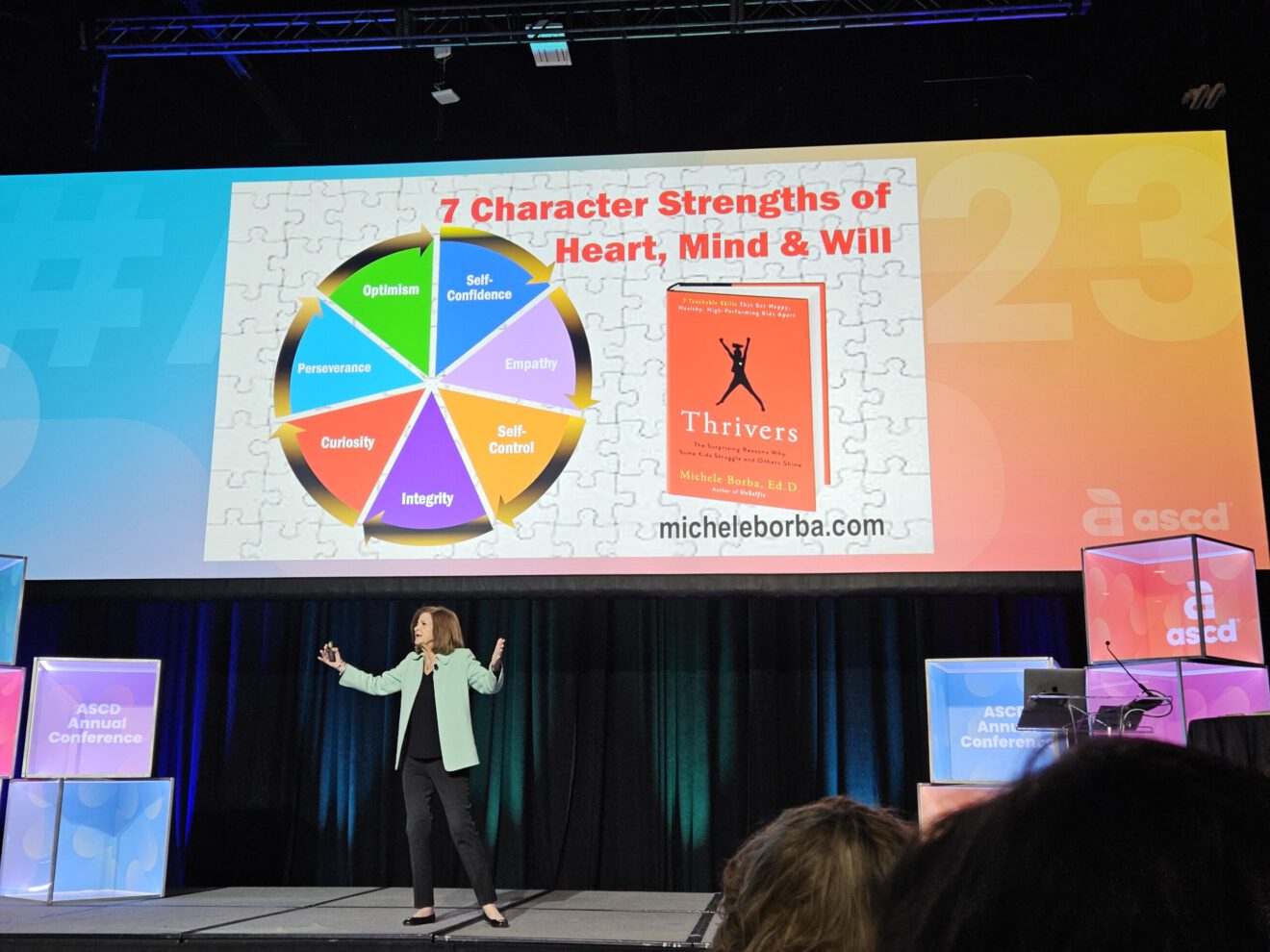

Test scores and grade point averages alone will not help students thrive in the world, Borba said. She outlined skills educators can weave into their instruction that will help boost students’ resilience, academic performance and mental health. The skills come from Borba’s book, Thrivers: The Surprising Reasons Why Some Kids Struggle and Others Shine.

Self confidence

Thrivers focus on who, not what, according to Borba. “Thrivers are kids who say, ‘I got this,’ – a child who has agency, a bounce back kid,” she said.

Teachers can help nurture student self confidence with practices that establish an environment of care and trust. She gave the example of her childhood teacher, Mrs. Fredrickson, who started each day standing at the door and asking each student if they wanted a handshake or a hug. The simple daily ritual – which the students dubbed “H and H” – built relationships with students and helped them feel seen. “Mrs. Fredrickson was a gold mine,” said Borba. “She started the day by creating trust and safety and security.”

Recognizing students’ strengths also helps build confidence, she said. She told about a high-school science teacher who uses colored index cards to help him learn about his students. He has one card for each student and assigns different colors to each class period. He uses the cards to take roll, filling them out with information he learns about his students – who they are, what they love, what they create. The exercise has helped him to better understand his students and give them meaningful praise they appreciate.

“Confidence – knowing what your strengths are. We thrive more when we have that,” said Borba.

Empathy

Thrivers practice empathy – they focus on “we” not “me,” according to Borba. She said today’s students need help cultivating this trait.

“It’s lying dormant,” she said, referencing data showing a 40% decline in empathy among American teens. She attributed the drop, in part, to students spending their days “looking down at screens and not up at each other.” What they need are activities that train them how to look up and interact with others.

Borba told of a history teacher who does daily “brain breaks” with his students. In this activity, students pair off with a partner (it could be the same person all day or all week), sit square to that person and have a 30-second conversation – maybe reviewing the next day’s assignment or discussing what might be on a test. The goal is to help them get comfortable looking at and listening to each other, without judgement.

Activities like this help students develop emotional literacy and concern for others. “The thing we have to remember is that empathy is a verb,” Borba said. “It’s got to be active. It’s got to be meaningful.”

Self-control

Thrivers can think straight and put brakes on impulses, said Borba. They are able to focus, self manage and exercise healthy decision making.

Borba spoke of Visitacion Middle School, in San Francisco, Calif. Violence is the norm for many students at this school. “You’re looking at a group of kids who text each other in the morning about which streets to avoid so they won’t be shot,” she said. “And by the time they walk into your classroom and sit down do you think they’re gonna be able to tune into your dynamic lessons? No.”

The principal and school counselor realized the students needed coping skills. They implemented a schoolwide “Quiet Time” at the beginning of each day. They found the time by shaving a few minutes from every class. During Quiet Time, teachers dim the lights and turn on soft music. Students can sleep, meditate or practice slow, deep breathing. The goal is to help them settle down and get into a mindset for learning.

It worked. An examination of data – pre- and post-implementation of Quiet Time – revealed that student behavior had improved. Suspensions and absences were down and classroom performance was up. Focus was better and test scores soared. News of the success got out and other neighboring schools implemented the practice.

Talk to students about why they’re doing this, Borba advised. It’s important they understand. Teach them how their brains react to stress and deep breathing, how these two affect executive function and what stress does to different parts of the brain.

And then weave it into your daily instruction. “Every day, a minute or two each day,” Borba said.

Perseverance

Thrivers finish what they start and don’t need gold stars, Borba said. Weaving one skill into your practice daily will demonstrate this for your students.

“That’s what teaches perseverance,” she said. “Now they have an expandable mindset to go ‘Oh! I gotta keep practicing, I gotta keep practicing.’”

A school in Temecula Valley Unified School District, in Temecula, Calif., has created “Thriver Squads.” Each month, the principal chooses one strength for the school to focus on. Then, every week, the students in the Thriver Squad meet at lunch to create a video on how to perform that skill. Teachers show the video during class time.

“I walk into every single classroom the first five minutes of the day and they’re practicing the skill,” Borba said. “The kids are so engaged, looking at the smartboard…at their peers who are teaching them the scale.”

Students aren’t born with this skill; they must acquire it. “Perseverance is one of those extraordinary superpowers, but you weave it in. And that becomes absolutely textbook perfect,” said Borba.

Curiosity

Thrivers are open to new experiences and ideas and are willing to take risks to learn and create, Borba said.

She spoke of a group of high school students who formed a book club for her book. They’re reading it and talking to their administrators about the skills they need to learn. Borba met with them recently, over Zoom. “Their first question is, ‘We just wanted to know why you wrote this for teachers and parents. Why didn’t you write this for kids? That’s what we need’,” she said.

Another book club includes students in the fifth grade. “They’re reading everything they can about curiosity from Thrivers,” Borba said. She will be holding regular Zoom calls with them. “They learn as much as they can about how to thrive and then they do an assembly for their parents and the assembly for parents is ‘Here’s what you need to teach us’ and the parents will come and give kids voice, agency.”

Integrity

Thrivers have strong moral codes, Borba said. They have moral awareness and identity and think along ethical lines.

“You’re dealing with a population of students who need to be deeper thinkers,” she said. “You’re dealing with a population of kids who can ask Alexa and Siri for anything. They don’t have to figure out what the answer is – just copy and paste from it. Yale says you’re raising really smart kids but they’re excellent sheep. They’re following along and they’re more risk averse.”

She told the story of Norm Canard, a history teacher in Kansas. Canard believed that history was among the best ways to learn about character. He wanted to teach his students that they could be changemaker and expose them to people of character.

Canard gave his students a project where they had to work in groups to find an example of a changemaker with exemplary character. A group of girls had trouble finding a subject so he directed them to a box that he kept in the classroom – a box where he collected stories of people of character. The girls found a story about Irene Sendler, a Polish nurse who served with an underground resistance group in Warsaw during World War II and helped rescue Jewish children from the Nazis.

The girls were enthralled with Sendler’s story. They discovered she was still alive and created a play called “Life in a Jar” to tell her story. They eventually made contact with Sendler and flew to Warsaw with Canard to meet her.

The girls’ project is an example of empathy and integrity, said Borba. “Here’s empathy and integrity and curiosity. Each one of these powers doesn’t work alone. You put them together and they become superpowers,” she said.

Optimism

Thrivers can find the silver lining in circumstances, said Borba. They think optimistically, communicate assertively and have a sense of hope.

“Every child and every grown up in the world needs is a ‘We got this and we’ll get it through it’ outlook,” she said. “Hope.”

Children who don’t have an optimistic outlook, who can only focus on and talk about the negative run the risk of falling into pessimism, according to Borba. “If we always say nothing but the negative, pessimism becomes permanent, pervasive and personal,” she said. “It’s one of the things that’s so deadly to our kids because it robs them of hope.”

Borba urged educators to teach students how to push back on negativity. She recommended doing an assignment where students – individually, as a class or as a school – come up with encouraging sayings that become personal mission statements. Have them write down those statements and practice saying that to themselves frequently. This practice of talking back to the negative helps build resilience, Borba said.

“Resilience is a mindset,” she said. “We gotta believe we can do it. It’s a process. It starts when our kids are young and it keeps on going the rest of their lives. Children who are thrivers are made, not born.”

Kanoe Namahoe is the director of content for SmartBrief Education and Business Services. Reach her at [email protected].