Ann Olivarius reflects on her role as a pivotal participant in the landmark US case Alexander v. Yale University, and her pioneering work to extend Title IX to cases of sexual harassment at educational institutions.

As Americans celebrate the 50th anniversary of Title IX, I am reminded of why I and several other young women used it to sue Yale University in my senior year back in 1977.

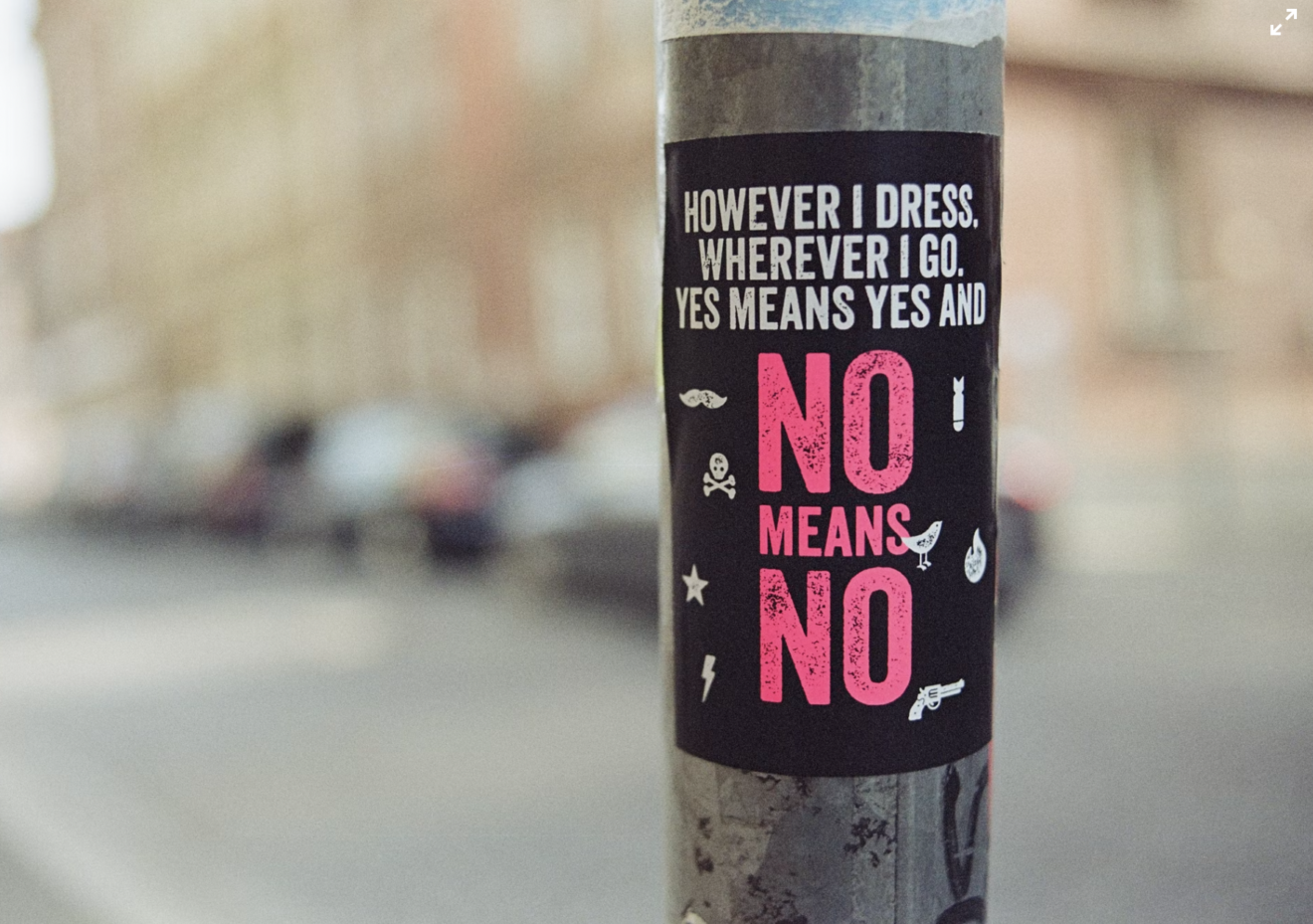

Title IX guarantees educational equality regardless of sex. Our lawsuit established that achieving this equality requires universities to reign in professors who pressure young women for sexual favors in exchange for grades and academic advancement. Since then, women have made a lot of progress in education. But after decades as a sexual discrimination lawyer, I know that Title IX needs an update.

Alexander v. Yale

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 barred discrimination based on “race, color, religion, or national origin.” It didn’t include sex. That’s why Title IX, passed in 1972, was so important. It bars sex discrimination in educational programs that receive federal funds, which includes almost every university, college and public K-12 school in the country.

Title IX requires women to receive the same opportunities as men from the playing field to the classroom. But I could see that clearly wasn’t true at Yale in 1974, so I helped found the Undergraduate Women’s Caucus. After hearing about predatory faculty targeting women students, we pressed the university to implement a grievance procedure. Yet the administration refused, stalled and even threatened to have me arrested on the morning of my graduation.

I sued, along with several other female students and one professor, contending that the permissive climate toward sexual harassment denied women an equal education and thus violated Title IX. The case is known as Alexander v. Yale.

Victory in loss

One of the plaintiffs was raped by her instructor; another was given a lower grade after rebuffing her professor’s advances. Most of our suit was dismissed because we had already graduated, which the magistrate ruled invalidated our complaints.

But in that loss was the win we sought. The judge affirmed our central argument, writing that “academic advancement conditioned upon submission to sexual demands constitutes sex discrimination.”

We asked not for monetary damages but that Yale establish a mechanism for hearing reports of harassment. Here, again, we won. The university set up procedures — today’s Committee on Sexual Misconduct. So have other schools around the world.

Reset

Unfortunately, sexual harassment and assault remain widespread and, by some measures, are getting worse. Title IX cases are multiplying: More than 1,500 are pending.

After 50 years, Title IX needs a system upgrade. The Biden administration — shortly to release its guidelines — has already taken steps to protect transgender students. Here’s what else it should do.

Duty of care

The basic problem with Title IX that I constantly encounter as a litigator is that schools are not held accountable for mishandling investigations. They can bungle evidence, lose files, not reply to student complaints and face no penalties. Title IX is called into play only when schools are “deliberately indifferent” to student complaints. This forbidding standard disadvantages survivors and effectively incentivizes schools to make “mistakes.” A better standard is the lower bar of “negligence.”

Similarly, schools today are liable only for misconduct that plaintiffs can prove was known to administrators. The guidelines should include misconduct administrators should have reasonably known about.

Another problem is that former President Donald Trump’s secretary of education, Betsy DeVos, weakened regulations, making it tougher for survivors to bring cases. For one example, harassment outside of official programs and properties — read “frat houses” — is now excluded. Yet fewer than 25% of undergraduates live in dorms. The rules should cover any activity and place connected to a program.

Independent Title IX offices

Title IX investigations are carried out by employees, who are torn between concern for students and job security. They are often pressured to pull fact-finding punches, an issue in the recent suit against Harvard.

To debug this system, the government should fund objective, third-party Title IX offices.

Heed survivors

The previous administration pushed a requirement that victims and their evidence undergo live cross-examination. Thankfully, the court pushed back. We need to be sure that due process does not intimidate victims from coming forward, increase their trauma and imply that sexual assault accusations are largely women’s lies.

Another DeVos change that should go is permitting schools to require that Title IX cases be settled by “clear and convincing” evidence — a high burden, one notch down from the bar in criminal court — instead of the “preponderance of the evidence” standard used in civil cases that is normally used for campus discipline.

Proactive policies

I want to see a shift in the attitude of schools from “What is the minimum I must do to avoid getting sued?” to “What steps can we take to make students safer?” President Barack Obama’s administration urged “proactive measures” to address sexual harassment. Biden’s campaign similarly promised more training for students and faculty, requiring schools to liaise with rape crisis and domestic violence centers, Title IX advisory networks and funding for student-led prevention programs. Let’s hold him to it.

Let‘s also see passage of the Gender Equity in Education Act of 2021, which would establish a new Office of Gender Equity that could spreadhead these efforts. It could also issue periodic report cards on how each school is preventing sexual misconduct.

Trauma-informed policies

Last, a new operating system for Title IX should fine-tune reporting procedures and require all relevant parties, from first-year students to senior professors, to undergo victim-centered, trauma-informed training, including the consequences of sexual harassment. I say this as a lawyer, and also a survivor of rape and sexual harassment myself.

Today

Fifty years on from the passage of Title IX, I look back with mixed feelings. It empowered women to speak out and hold the guilty to account. But it pains me to see young female students and faculty continue to suffer from a campus culture that often looks little different to what I experienced years ago.

We thought back then that Title IX and Alexander v. Yale would make women equal.

We still have a long way to go.

Ann Olivarius is a founding partner of McAllister Olivarius law firm in New York. She and Gloria Steinem, author and feminist icon, are speaking together via Zoom Friday, April 15, at 7 p.m. ET.

________________________________

If you liked this article, sign up for SmartBrief’s free email newsletter from ASCD. It’s among SmartBrief’s more than 250 industry-focused newsletters.

More from SmartBrief Education:

- 5 ways new school-home communication meets family, staff needs

- 5 virtual-classroom tools to foster authentic connections

- Changing the classroom experience with instructional audio

- Powerful social media solutions for students

- How comics curriculum boosts SEL

- 8 ways to make vocabulary instruction more effective