As more educational content is created in digital formats and content that was originally not digital is digitized, it is important to consider issues of accessibility for everyone who needs to access those materials.

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1972 is enforced by the US Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights. That office says accessibility means “those with a disability are able to acquire the same information and engage in the same interactions — and within the same time frame — as those without disabilities.” This guidance is over 10 years old; it has been distributed to every educational institution. Moreover, when revisions to Section 504 become available for public comment soon, this definition is not expected to change substantially.

OCR does not monitor the vendors that produce digital educational materials. Instead, it monitors the educational institutions that require teachers to use and families and children to access the digital materials to get an education. Therefore, it is critical for administrators and school leaders that have purchasing power to understand accessibility concepts so they can ensure the materials they buy meet legal requirements so the students they serve can use the materials to learn.

Why accessibility isn’t straightforward

Ensuring accessibility is also complicated because software that is advertised as accessible or features that are advertised as accessibility features may not serve young learners as intended.

For example, text-to-speech technologies can be a boon for students who have low vision or other reading difficulties. However, many text-to-speech programs require students to perform many steps to activate these technologies. We have seen classrooms where students were required to:

- Determine whether the text-to-speech technology is available on the machine they are using.

- Click on the text-to-speech technology.

- Click on the icon to access text-to-speech.

- Create a box over the text they want read.

- Monitor how much text they choose to have read to them at a time. (Otherwise, the text might be read too quickly for their comprehension.)

If students choose too much text or become impatient with themselves or the program, they lose interest and disengage with the task. What should have been an accessibility support involved multiple steps for young people to learn and multiple tasks for them and/or a teacher to simultaneously monitor.

As a second example, many learning management systems contain programs where young people are supposed to access and write on worksheets teachers have uploaded to folders. Again, this requires many steps: finding the right folder, opening the folder, writing on the document and saving it correctly.

The writability features included in these programs as supports also can also be problematic. Many children struggle to manipulate peripheral mice and trackpads to make boxes the right size and then toggle back and forth between adding boxes and adding text. Doing the resizing and toggling tasks can take longer than responding to items.

Once again, there are too many opportunities for young people to become frustrated with these tasks and disengage.

How to “step up” to accessibility

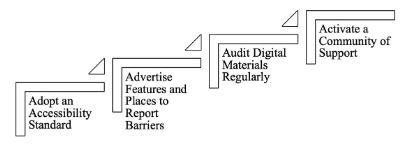

To make better use of digital instructional materials funds, we recommend a four-part way to step up to accessibility. These are based on the recommendations that OCR often gives to help resolve complaints, but we see them as good guidance for avoiding complaints as well.

First, adopt an accessibility standard. Second, advertise when, how and to whom to report barriers. Third, conduct regular audits of materials. Fourth, build communities of support that include administrators at other schools, vendors, parents and others.

Adopt an accessibility standard

Section 504 does not currently name a specific accessibility standard. However, the broadly accepted standards developed by an international consortium are known as the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines. Currently, version 2.1 AA of WCAG is used by many educational institutions.

Though not a set of accessibility standards and not as technical, the 4A Framework for Evaluating Digital Instructional Materials might provide some initial guidance to administrators and teachers about accessibility and other important aspects of choosing digital materials.

Administrators should identify a set of standards, adopt them and begin coordination efforts to ensure other school leaders and employees know the standards.

Advertise features and places to report barriers

Section 504 requires the institution to identify a Section 504 coordinator and to annually publicize the name and contact information of the Section 504 coordinator within the institution and within the community. A school also must create and publicize a grievance policy for individuals who seek redress for accessibility problems. A grievance process helps reduce the potential for complaints to go to OCR.

In addition, institutions should be proactive about publicizing the efforts they have made to ensure that digital instructional materials are accessible. Put this information on websites and in newsletters (but be sure those are accessible too).

Audit digital materials regularly

Add an accessibility review to purchase procedures so that all new products purchased by the institution will be reviewed in a timely manner. If the material does not meet the institution’s accessibility standards, it should not be purchased.

Simultaneously, improve awareness of what constitutes accessibility for teachers so they can audit instructional and communications tools they use. Voluntary Product Accessibility Templates can provide some information. However, VPATs written by marketing teams may not be as helpful as VPATs written by engineers, so VPATs can only be one source of information about accessibility in an audit. Again, the 4A Framework for Evaluating Digital Instructional Materials has a checklist with some starting questions.

Audits might also include reviews of assistive technologies and other devices, such as headphones and keyboards with specific features that are or can be made available to those who might need them.

Activate a community of support

Provide professional learning opportunities about accessibility for all employees. Ultimately, accessibility is a shared responsibility, but school leaders play a major role in setting the tone and setting up procedures.

Because Section 504 and the Americans with Disabilities Act do not yet apply to the producers of instructional materials, it is imperative for administrators to find opportunities to share information with other educational institutions about where to find accessible materials. Strength in numbers is crucial when there is a need to encourage a vendor to make materials more accessible.

Administrators have much to worry about in today’s school environments. If you plan in advance based on the steps outlined here, accessibility complaints likely won’t be on the list of concerns. Hopefully, this guidance will make supporting young people and those who work with them — teachers, parents and others — a more successful endeavor.

Mary Rice is an associate professor of literacy at the University of New Mexico. Her research focuses on the shared roles and responsibilities for accessibility in digital learning settings. Ray Rose is an accessibility evangelist and civil rights advocate in Corpus Christi, Texas, who works with many organizations, including the Texas Digital Learning Association.

Opinions expressed by SmartBrief contributors are their own.

_________________________

Subscribe to SmartBrief’s FREE email newsletter to see the latest hot topics on EdTech. It’s among SmartBrief’s more than 250 industry-focused newsletters.