In 2003, Radio Shack operated nearly 7,000 stores (and a store within 3 miles of nearly every American) and generated close to $5 billion in revenue. A dozen years later, the company filed for bankruptcy.

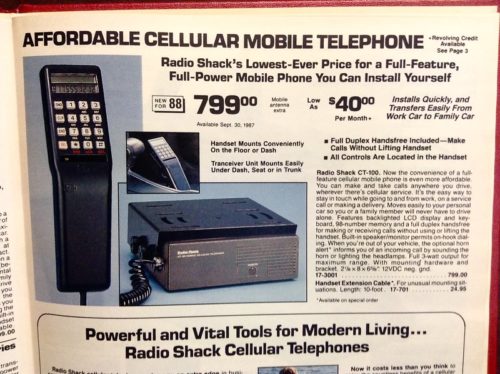

What happened to Radio Shack? Several things conspired to take it down, from focusing too much on a single product category (rapidly commoditizing cellphones), to suffering a shortage of operating capital, to trying to adjust to a revolving door of seven CEOs in 10 years.

But ultimately, what happened to Radio Shack was that it simply got outmoded by a company that at the time was also doing about $5 billion in revenue, Amazon, which is now pushing 100 times that amount.

In the old days (i.e., when I was a teenager), if my dad needed an esoteric battery or some speaker wire, he sent me to Radio Shack. I paid whatever they asked, because there was no alternative and I had no idea what that battery or speaker wire should cost anyway.

Today, if I need a rare battery or something for my wireless home entertainment system, I can compare prices and have them delivered right to my door with just a few clicks. Radio Shack, like speaker wire, simply became obsolete.

“Planned obsolescence” is a term of derision directed at companies who are thought to deliberately ensure their products will become old, tired, broken or useless before their time, forcing customers to replace them more frequently than they should.

There is some debate as to whether manufacturers knowingly do this; in 2020, Apple settled a class-action lawsuit over what was playfully called “Batterygate.” The company was accused of intentionally slowing down the processor speed of older iPhones when their operating systems were being upgraded. Regulators in France fined the company for a similar issue. (Apple claimed that the performance slowdowns were the result of diminishing battery performance rather than the software upgrades.)

Computer-printer manufacturers have also been accused of planned obsolescence, not so much related to the printers themselves but the ink cartridges. They follow the old “give away the razor and make money on the blades” strategy of selling the hardware cheap in order to lock people into purchasing specific — and expensive — ink cartridges that run out of ink far too quickly. Some cartridges even have built-in smart chips that disable them when the ink is running low — but not out — for “quality control” reasons. Grr.

Textbook publishers, fashion brands, software companies, carmakers and television manufacturers, among many others, have faced similar accusations of planned obsolescence. Some of the claims probably have merit, and the offending companies deserve any disapprobation they generate.

When is planned obsolescence good?

But planned obsolescence isn’t always bad; it depends on whose ox is being gored. Apple planning the obsolescence of my iPhone? Yeah, that’s bad. Apple planning the obsolescence of the iPhone? That’s imperative.

Theodore Levitt was a celebrated editor of the Harvard Business Review, a professor at the Harvard Business School and author of several seminal books on marketing. He cautioned that companies themselves must regularly and as a matter of course plot the obsolescence of that which now produces their livelihood. “If a company’s own research does not make a product obsolete,” Levitt said, “another’s will.”

If only Radio Shack had listened to the good professor. Not that it would have been easy or inexpensive to change its business model, but at some point in the company’s healthy and wealthy past, it would have certainly been doable. The brass at Radio Shack just couldn’t, or wouldn’t, see it.

Neither could the brass at Blockbuster, which notoriously refused to purchase Netflix in its early days and pulled the plug on its own nascent streaming service. Borders Group saw the internet coming and infamously outsourced its online sales to a little startup called (you guessed it) Amazon.

As of late 2021, taxi medallions in New York City went for a meager $80,000, down from $1 million at their height in 2014, thanks to Uber and Lyft. Just as our lives unfold as a result of the decisions we make (or avoid making) along the way, so also do our companies.

General Catalyst partners Hemant Taneja and Ken Chenault (formerly CEO of American Express), drive the necessity of planned corporate obsolescence home well:

“Enduring companies are not one-trick ponies. Companies with a long-term vision must accept that as the market changes around them, systemic transitions – transformations – are a fact of life. What was once novel becomes a commodity over time.”

Indeed, it does. Apple may or may not have been practicing planned obsolescence with respect to its iPhone upgrades, but it absolutely practices planned obsolescence with respect to itself. Apple has been the world’s most admired company for 15 straight years — an impressive feat — but what’s even more impressive is that roughly 90% of its revenue comes from products that didn’t exist when it first topped the list.

The company is unusually adept at planning its own obsolescence, and everyone benefits.

What is it that’s producing your livelihood today? No matter how inventive or productive it is, you can be certain that it won’t be tomorrow. Or maybe the next day. If you’re not planning your own obsolescence, someone else is.

Each month, When Growth Stalls examines why businesses and brands struggle and how they can overcome their obstacles and resume growth. Steve McKee is the co-founder of McKee Wallwork + Co., a marketing advisory firm that specializes in turning around stalled, stuck and stale companies. The company was recognized by Advertising Age as 2015 and 2018 as Southwest Small Agency of the Year. McKee is also the author of “When Growth Stalls” and “Power Branding.”

If you liked this article, sign up for Business Transformation SmartBrief. It’s among SmartBrief’s more than 250 industry-focused newsletters.