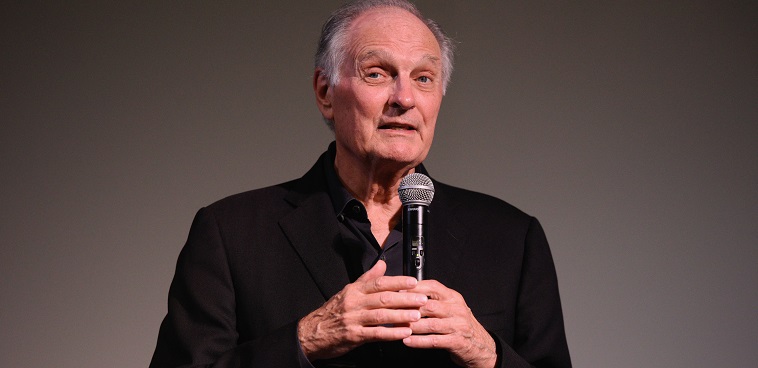

I recently attended an event where Alan Alda was interviewed, specifically about his recent book on the “art and science of relating and communicating,” which is based on the work of his Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science.

Alda, unsurprisingly, was sharp, funny and engaging. He also talked relative little about his acting career and more about his work in helping people, particularly scientists, communicate more effectively and with empathy.

He lived this philosophy during the talk, as he engaged the interviewer with his own questions and actually answered audience questions instead of using them as a springboard to talk about something different. With certain questions, such as from a woman who had done research on helping librarians communicate more effectively, Alda had a question of his own — the first time I can recall seeing that from a headlining speaker.

(As I was finishing this post today, Alda put his personal theories of communication to the test in announcing, in good humor via Twitter, that he has Parkinson’s.)

But I’m writing about the event now because of a key distinction Alda made in response to a question. The questioner, he said, was asking about how to carry out a communications plan, whereas his book and work was focused on communication.

This distinction can be lost in a busy world where companies, politicians, celebrities and ordinary citizens are always speaking, posting and arguing — when they aren’t defending or apologizing for something they’ve previously said.

Communication and communications each has its place, but we shouldn’t conflate them. The communication Alda speaks of is how you or I interact with people: how we listen to them, how and what we ask, how we absorb what they say and then how we respond — and the tone, wording, volume, posture and aggression of those responses.

Communications is tactical, sometimes even strategic, but no communications plan can substitute for the actual communicating.

This post, for instance, is me hoping to communicate with some of you. My writing of a one-pager on the strategy for this leadership blog in 2019 would be communications. My carrying out this hypothetical plan with my co-workers and others would require a lot of communication.

The point here is not that one of these is good and the other is bad. The point is that we are prone to shy away from communicating by passively invoking communications, and we are prone to communicate blindly and screw up when a little communications strategy would have helped. Some common statements that illustrate the misuse of one of the other:

“Let the comms team handle that.”

“We’ve got to get a statement out to show we’re on top of things.”

“We’ve written X down in a handbook.”

“I’m sorry for anyone who was offended by …”

Many companies need a comms team and/or a communications strategy. Saying something as a public-facing person or firm is often better than hiding from whatever the news is. Handbooks have their place, too! But none of these things is an action or a living thing — we must still speak and write and act, and that’s where communications strategies succeed or fail.

For instance, how will you take that handbook and live its values, and help others do the same? If you think the handbook is bad, how will you win the argument and get the backing to change it?

Another case where communications doesn’t translate into good communication is the memo. How often do memos and policy declarations clearly think only of the organization’s most immediate need and not the real-life experiences of the people affected (employees or customers)? How many of these memos introduce new confusion or have unintended — and often unaddressed — consequences?

The same problems can be found in our personal communication. How often do we speak or write or type without thinking? How often do we attack with our words instead of taking the time to calm ourselves, to listen, to try and understand and empathize with the other person? What if we had a plan that we could apply as needed?

The good news is that communications and communication can work wonders in tandem. Ever been to an event that goes off smoothly despite a crowd of people, many speakers and caterers and other staff busy throughout? Those people had a communications plan (among other plans) and then communicated well as the event went off. That’s just one example.

The short lesson is this: We all need to understand why good communication is necessary and fruitful, understand when good communications is needed and understand the right ways to use each.

Gaining this knowledge and applying it will take practice, trial and error, and study. However, if Alan Alda can be passionate about communication at his age, with all his success, then so can we.

James daSilva is the longtime editor of SmartBrief’s leadership newsletter and blog content, as well as newsletters for distributors, manufacturers and other professions. Before SmartBrief, he was a copy desk chief at a small daily New York newspaper. Contact him @James_daSilva or by email.