Financial literacy was not a topic discussed at home or at school when NFL wide receiver Arrelious Benn was growing up.

“I never had anybody talk to me about financial literacy,” said Benn during an interview with SmartBrief Education. The soft-spoken athlete, one of five boys, was raised by a single mother in Washington, D.C.

“You always hear them talking about, ‘Hey, you gotta go out there in the world; you gotta make money,'” he said. “Everybody can make money and get money but what do you do with money? No one ever told me, ‘This is what you need to do with it.’ Obviously save. But how do you save?”

Benn’s situation is not unique. Findings from the 2015 Program for International Student Assessment show that 22% of teenage students in America do not have basic financial literacy skills; just 10% have high financial literacy skills. Among US students with high financial literacy, only 3% came from disadvantaged schools while 45% were from affluent schools. Students with high financial literacy are more than twice as likely as their less financially literate peers to save their money for something they want. Students with low financial literacy are more inclined to buy something they want with money that has been allocated for different purposes.

Benn aims to help correct this issue. He has returned to his home town with a drive and program to teach young people the principles of wise money management.

I’ll take Savings and Investment for $500

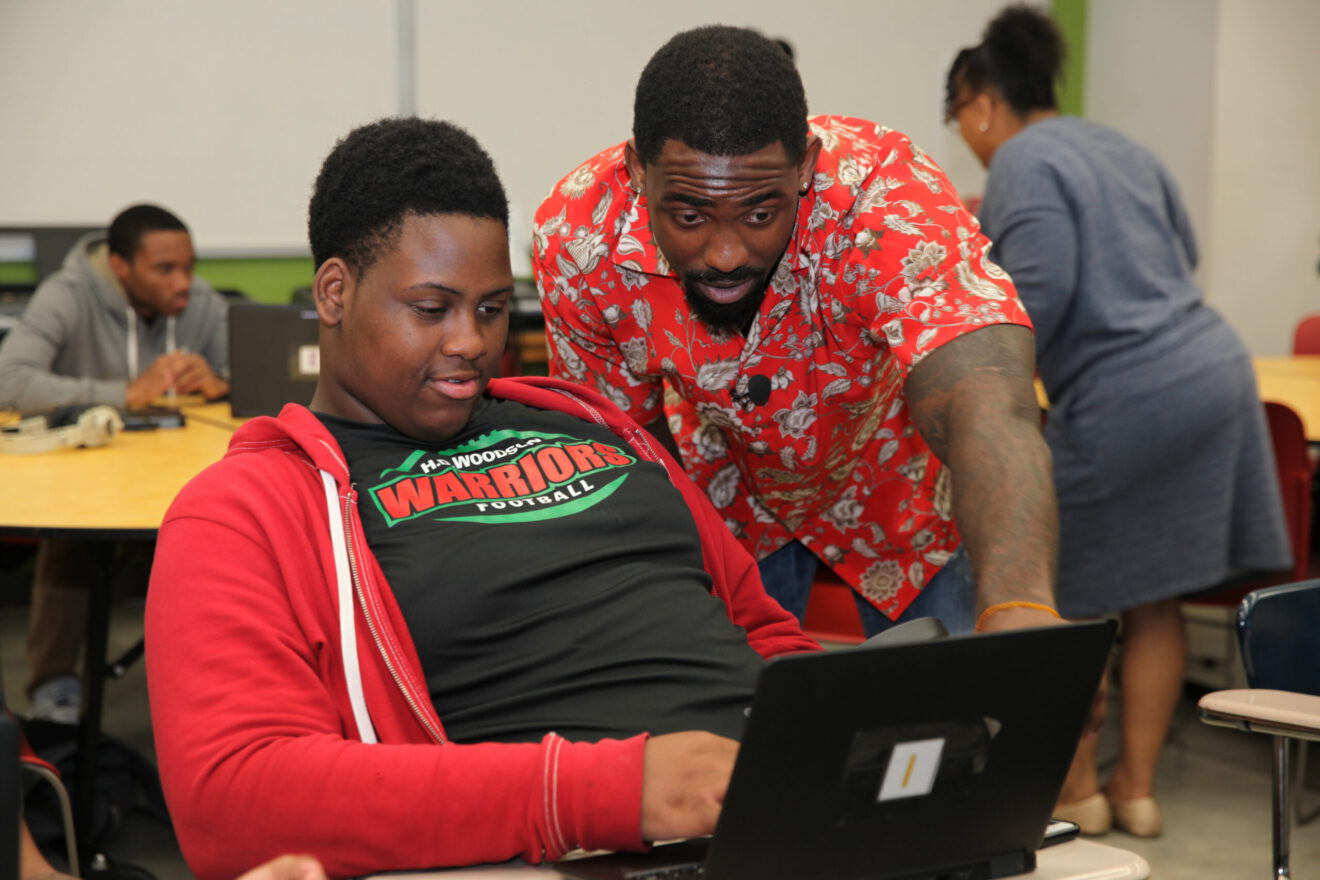

Benn recently visited H.D. Woodson High School, located in northeast Washington D.C., to work with students on a financial-literacy platform — called Phone Home Financial Scholars — developed by education-content provider Everfi. Benn has partnered with Everfi to evangelize the message of financial education.

Students do course modules online on topics including building credit, managing debt and buying or renting a home, explained Benn. “They’re learning how many times you have the opportunity to check your credit score per year [and] that just because you have a credit card that doesn’t mean that it’s free money,” he said. Other modules cover savings, banking, college financial aid, insurance and taxes, consumer protection and investing. Students can also take notes, earn badges and plan their financial goals in the platform.

Benn’s visit included a game called Financial Jeopardy. Benn acted as the game host, posing questions to the students on topics such as interest rates, savings programs, credit score ranges and financial aid options, among others.

“Their reaction to the Jeopardy game was amazing; they were really competing about it,” Benn said. “[There were] not hard but medium level questions for them to answer and they did pretty good with it, without them really having that basic financial background.”

Benn also spent time sharing his financial experiences with the class and then talking with students individually about the program. His goal, he said, is to find ways to make financial education important to them.

“I was in those kids’ shoes not that long ago,” Benn said. “[I want] them [to] understand that this is something I had to learn, we all have to learn it. Let’s try to learn it together.”

Tackling the financial literacy gap

How can we help close the financial literacy gap among youth? Benn offers these suggestions.

Focus on habits. Students need to know that habits — not financial windfalls — are the key to financial stability and wealth, Benn said. The Everfi course modules include activities that teach about responsible habits including managing a checking account and putting money aside for savings on a regular basis.

Students need to know that their decisions will follow them, for better and for worse, Benn said. He told about a teacher at Woodson who used the example of cell phones to illustrate the consequences of decisions. She talked about a student who has cell service with T-Mobile but wants to change carriers so he can purchase the new iPhone. He decides to leave T-Mobile, without paying the bill.

This student has no idea how this decision can affect him, Benn explained.

“[He] may not even pay that bill thinking, ‘Ok, I’m just leaving a bill,’” Benn said. “But you also have credit — and credit is your credibility. I want kids to understand that.”

Keep it simple — seriously. Financial concepts are tough to understand, Benn said, and even adults struggle with it.

“I [have] talked to a lot of people who are years older than me — it’s crazy some of the things that they don’t know about financial literacy,” said Benn. “It’s not just the kids; it’s everybody.”

Benn recommends starting with simple concepts and working up from there. The Phone Home Financial Scholars Program focuses on concepts such as banking, credit score, consumer protection, insurance, taxes, investment, payment types and the differences between renting and owning property.

“When it comes to living it — understanding — you need the basic things,” Benn said.

Create a safe environment. Students can be intimidated by the concept of finance and might be unwilling — or not know how — to ask questions, said Benn. Creating an environment where it’s OK not to know can go a long way in easing students’ tensions and uncovering gaps in knowledge.

“Kids want to know, but they don’t know how to ask,” he said. “I tell kids, ‘It’s OK if you get it wrong or if you get it right.’ I always tell them, it’s always an uphill battle to have to learn financial literacy. There is no such thing as a dumb question when it comes to finances.”

Start at home. Financial education should begin at home, and early, Benn said. He has already started teaching his young daughters about money.

“I have a 3- and 5-year-old and I was teaching them about coins — the currency of coins, understanding what a penny is, a nickel,” Benn explained. Older students, who receive allowance or work, should learn how to manage — save and spend — that money. Routine tasks such as grocery shopping are good opportunities to talk about credit cards, what items cost and sales tax.

“It doesn’t have to be something that’s structured,” Benn said. “Just pitch it out there; throw it in front of them. Have that topic and discussion.”

He recalled that while his mother did not have a great deal of financial knowledge, she made a point of sharing her experiences and teaching him and his brothers what she did know.

“My mom did help me open a bank account and told me [to] be aware of what I spend money on; that was months before I went off to college,” he said in an email to SmartBrief. “I recall my mother telling us certain things she wish[ed] she didn’t do and should have done; this was her way of telling us about finances.”

Be open and honest. Benn encourages educators and other adults to share struggles they’ve had with money. Hearing about these experiences can help students embrace the importance of responsible financial habits.

“We need to have open discussions about [money],” said Benn. “If I came out and told kids that I had misfortunes with financial literacy because of the basic knowledge I didn’t [have] about it, then they’d want to be more open to it.”

Benn acknowledges that finances are a touchy subject but maintains that it should be front-and-center in classroom conversations, alongside other difficult topics.

“Crack it open and just have that open discussion,” said Benn. “We gotta talk about some of the topics that are hard to talk about. We can talk about sex and drugs; we should really be able to talk about financial literacy.”

Kanoe Namahoe is the editor of SmartBrief on EdTech.

____________________________________________________________________________

Like this article? Sign up for SmartBrief on EdTech to get news like this in your inbox, or check out all of SmartBrief’s education newsletters, covering career and technical education, educational leadership, math education and more.