From pre-kindergarten through third grade, students are supposed to learn how to read. Fourth grade is the watershed year when teachers turn that model around and expect students to read to learn. The recent spotlight on reading scores has prompted an intense focus on those pre-K-3 students to make sure they’re ready by fourth grade.

Solutions for them are plentiful: The science of reading. Intensive tutoring. Summer programs. More teacher professional development. State laws requiring retention for third-grade students who aren’t proficient in reading by the end of the school year.

But what about the decades’ worth of students who were, and still are, passed into fourth grade and beyond when they can’t read at — nor often anywhere near — grade level? For these students, the inability to read well throws up a roadblock in front of every school subject: the instructions for a science experiment. The words in a math problem. The title of a song in music. As they get older, a menu, job application, street names or text message might as well be in a foreign language.

To get ahead, these older students are often given Dr. Seuss and Bob Books to help them learn. Sarah Fennelly, M.Ed., a reading specialist for fifth through eighth grades at Stoneham Central Middle School in Massachusetts, says some students “get frustrated that they would have to complete ‘baby work’ and just put their head down and refuse to work.”

“This tends to be more common than actually expressing their feelings, because I think often they don’t really know and aren’t really thinking about the future; they are just trying to fit in at school day to day, and that takes up a lot of mental energy,” she says.

Such heart-rending stories — including Molly’s in the 1990s and Sterling’s in the 2020s — show that, year after year, these older students continue moving ahead in grades despite being left behind in skills. Their embarrassment soars while their self-esteem plummets.

But why?

We’ve known since at least 2011 that such students are four times less likely than their reading-proficient peers to earn a diploma. Eight years later, the National Association of Educational Progress, whose assessment is dubbed the nation’s report card, noted that two-thirds of US students can’t read at a proficient level. Today, more than a third basically can’t read at all. Here’s the breakdown:

- 67% of 4th-graders weren’t proficient in reading in 2022. 37% couldn’t read even at NAEP’s basic level.

- 69% of 8th-graders weren’t proficient in reading in 2022. 30% of 8th-graders couldn’t read at the basic level.

- 63% of 12th-graders were not proficient in reading in 2019. 30% of 12th-graders didn’t meet NAEP’s basic level.

(The 2022 scores for 12th graders aren’t available until the end of this school year. All data from NAEP.)

“Appalling and unacceptable” are the words US Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona used in a statement when the NAEP report was released in October. “But raising the bar means we can’t just be satisfied with pockets of excellence for some. … Now is the time for bold action.”

At least two companies are trying something new, reaching out with new tools for struggling older readers.

Easy-to-read books that meet the backpack test

When Louise Baigelman, fresh out of college, was teaching middle school through Teach for America in Boston, many of her fifth- and sixth-grade students had learning differences or were English language learners. “They could not read above a very basic level, and my goal was to support them. But I couldn’t find books for them that weren’t very much baby books, like ‘The Cat in the Hat’ and ‘Curious George,’ ” she said.

“Nothing exists yet that is very targeted at [grades] three to 12, especially eight to 12, that applies the curriculum that works in K-3 with some nuance and materials that go with it. Teachers need a classroom library or supplemental books.”

She wondered: How do we “fix that chunk of time between fourth grade and ‘You’re going to end up on welfare’ ” to change that statistical illiteracy trajectory?

So Baigelman created Storyshares, a library of specifically crafted paperbacks and ebooks using a high/low concept: higher-interest topics, shorter chapters, shorter sentences and more basic vocabulary. The books feature diverse characters of varying ages and engaging, relatable topics, such as two friends’ love of cooking, grief, climbing Mt. Fuji, sexual assault or an exploration of a career. Baigelman wants every book to meet the backpack test — written and designed so older students aren’t embarrassed to pull them out of their backpack in front of peers.

The company uses contests to find and nurture diverse writers around the globe, some who are teens and young adults who may not have been published before. They can use Storyshares’ ebook platform with built-in feedback that helps them stay on track with a reading level and assists in other writing areas.

Adding science of reading to age-appropriate content

With a library of more than 500 available books, Storyshares has recently been working on Decodables, a new group of books that also have higher interest but are subtly “based on exact phonics patterns and sequences that scaffold — short A in one chapter and short O in the next,” she explains. These can supplement Wilson systems or other intervention programs a teacher may already be using.

“Those curriculums have text to teach it and a little lesson, and then it’s on to the short O. You can teach the short A, but you can’t teach someone to LOVE to read with that. They can’t really deepen learning with that practice,” Baigelman says.

She believes her books for older students can. All Storyshares and Decodables books can be read with an online e-reader tool that lets students change colors and font size; click on a word or picture for definition; listen and have it read aloud; and use color gradients to help with visual tracking.

A comprehensive educators’ companion book teaches teachers the key literacy components. As Baigelman notes, “Middle- and high-school teachers came to teach literature and now have to teach literacy. Fluency, background knowledge and comprehension also are really key components. The guides teach about some of those concepts and offer concrete strategies and activities.”

An illiteracy nonprofit in New York City called Read 718 is aimed at students in grades three through eight who are two or more years behind in reading. Rachel Fucci, senior program director, gave Decodables a try last fall. “It just felt like a resource that we had been looking for for a long time in terms of meeting students at an intelligent level and engaging them,” Fucci says.

She gave one to a creative fifth-grade boy who was more into games and YouTube than reading. “I said, ‘We just got this series, and this is the first book. I really want you to give me your review on it. Let me know what you think.’ He was really excited to take on that responsibility. He finished [that 50-page book] in one day, in one sitting. … I said, ‘What would you give it out of five stars? And he said, ‘10 stars!’ He was just so excited to complete it, and I had never seen him read that much that quickly.”

Fucci says the student likes the interconnectedness of the stories.

“He’s able to track where certain characters are coming from, and he knows how they’re all connected to each other. I’ve never seen him that engaged and excited about a series before. He’s been a student [with Read 718] for two years now, and I felt like it was really reaching him,” she says. The boy’s family also sent Fucci a happy note last fall to say they’d gone out for family karaoke, and “he was reading all of the lyrics on the TV.”

Fennelly, the Massachusetts reading specialist, participated in the Decodables pilot program last fall and shares a similar story about an eighth-grader who will read a whole Decodables book all at once, and she credits the “combination of decodable text, diverse characters and age-appropriate topics.”

What comes after decoding for older students?

Decoding words is crucial, but it only gets students so far, asserts Julie Van Dyke, a senior scientist at Haskins Laboratories, now part of the Yale Child Study Center, who is chief scientist at Cascade Reading. After transforming early reading — the sounds and how they map to letters — “what we need now is help to transform the second half of reading instruction that focuses on the linguistic essentials of the language. What teachers usually do is they focus on vocabulary because that’s easy to teach. Cascade Reading is really filling a void: We focus on the linguistic structure of the sentences and the text,” she explains.

Van Dyke talks about the differences in written and spoken languages. Our writing, with all its clauses and embedded clauses and conjunctions, is far more complex than the way we speak. “So a reader, when they’re focusing on most of their learning coming from the written word, needs tools to be able to process that complicated grammar,” she says.

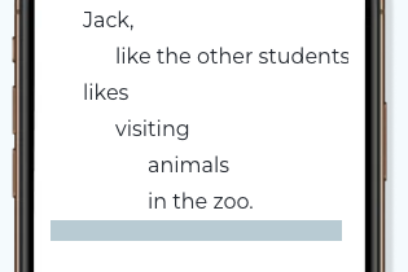

The Cascade Reading web-based tool takes a sentence and cascades it down a page in parts to help readers see which parts of the sentence go together. It’s a modern-day version of diagramming sentences, which is helpful when figuring out more complicated chunks of text. (Think science textbooks or apartment rental agreements or websites’ terms of use.) This helps the older students decode a sentence, rather than a just word, because seeing how a sentence is constructed helps the reader pick apart what it really means.

Cascade handles the part of grammar most of us hated — remembering what a predicate, preposition and other parts of speech were — and puts them in place with colors and indentations instead of labels. Van Dyke mentions an example using the preamble to the US Constitution:

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

Cascade would trickle those words down the page with varying degrees of indentation to show the subject and predicate — “We the people” and “do ordain and establish” — as the main parts of the sentence, and then how the rest just modifies them.

Here’s an example I tried.

The people at Cascade believe that revealing sentence structures this way increases syntactic awareness and helps with intonation, stress, pauses and more. These can not only increase comprehension but provide another entry into understanding and fluency for readers of all ages, those who are English language learners, those with developmental or emotional challenges and more, Van Dyke says. Repeated reading this way trains the brain to see sentences correctly, she says.

The product is new, and the company’s studies (submitted for peer review) thus far show a boost in confidence in the youngest readers, better comprehension and prosody in fourth- and fifth-graders, and benefits for university students in Chicago whose first language is English, Korean or Mandarin.

Cascade, which uses a natural language processing artificial intelligence, works with a Chrome browser add-on. Van Dyke says the company can take any book a teacher or school has digital rights to and put into Cascade for them.

A few other companies are working to update their literacy libraries with more age-appropriate practice content for older students. Perhaps others will come up with additional technologies aimed specifically at these students.

Opinions expressed by SmartBrief contributors are their own.

_________________________

Subscribe to SmartBrief’s FREE email newsletter to see the latest hot topics on edtech. It’s among SmartBrief’s more than 250 industry-focused newsletters.