Attribution: Map by Hal Jespersen, http://www.posix.com/CW (via Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license)

Attribution: Map by Hal Jespersen, http://www.posix.com/CW (via Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license)

One hundred and fifty years ago this summer, the Battle of Gettysburg turned from a potential Confederate victory to stunning defeat due to Gen. James Longstreet’s poor negotiating skills.

At the beginning of their classic, “Getting to Yes,” authors Roger Fisher and William Ury note that we are all negotiators, every single day. But most of us lack an actual method for negotiations.

In our daily work lives, we deal with colleagues more than folks on the outside, and it seems downright mercenary to approach our interactions with them as a negotiation. But what happens when we become convinced that a colleague or boss is taking the organization down the wrong path? How do we convince them to change their plan?

To bring this question alive, how might our world today be a different place had Longstreet been able to persuade his boss, Gen. Robert E. Lee, to rethink the attack we call Pickett’s Charge?

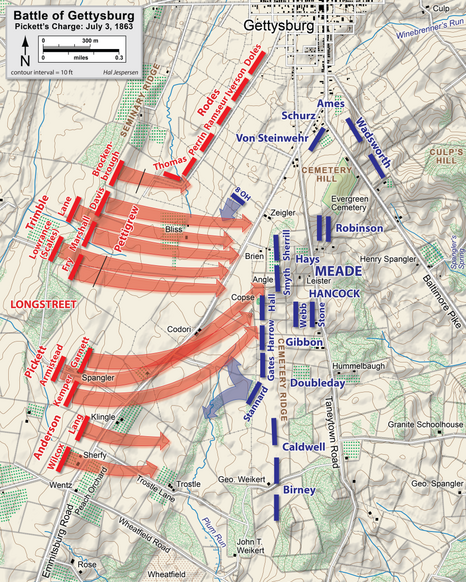

On July 3, 1863, Lee faced a pivotal decision. After two days of fighting at Gettysburg, Lee had decided to order 15,000 of his men to make a frontal assault on the Union lines in a gambit to win the war in one fell swoop.

Longstreet was incredulous, noting later, “I said, ‘General, I have been a soldier all my life. I have been with soldiers engaged in fights by couples, by squads, companies, regiments, divisions, and armies, and should know, as well as any one, what soldiers can do. It is my opinion that no fifteen thousand men every arranged for battle can take that position.”

To Longstreet’s chagrin, Lee replied, “The enemy is there, and I am going to strike him.” In his memoirs, Longstreet noted, “Nothing was left but to proceed.” Of the 15,000 men who began that charge, half ended up killed, wounded, or captured in what has to be described as one of the worst decisions of the war.

What Longstreet needed was a way to negotiate with and persuade his boss that there were better alternatives. What would it look like if Longstreet had been followed this plan?

- Figure out your target outcome ahead of time.

- Ask for more than your target outcome, but not outrageously so.

- Make several small concessions.

- Determine your bottom line ahead of time.

- Say “Yes, if” rather than just “yes” or just “no.”

- Be aware of your ego.

Now put yourself in Longstreet’s shoes. Did Longstreet identify a targeted outcome ahead of time? Yes and no. He encouraged Lee to move around to the right of the Union Army and take up a position nearer Washington, D.C., forcing the enemy to attack. But Longstreet had been making that argument for three days to no avail. It was stale at this point, and thus an ineffective target.

Did Longstreet ask for a bit more than his targeted outcome so he had room to make small concessions? No, he did not. He failed in two ways here. First, Longstreet asked for exactly what he wanted, and consequently had no room to maneuver when Lee said no. Second, he knew from the past three days that what he was asking for was, in Lee’s mind, outrageous. It was outside the limits of Lee’s reality.

Longstreet also failed to establish his bottom line ahead of time. When Lee put his foot down, Longstreet gave in. Some argue that in a military hierarchy Longstreet would have been insubordinate to continue resisting Lee’s plan. But remember that the result of this decision was 7,500 casualties, and ask whether Longstreet had a duty to continue trying to change Lee’s mind.

Our central piece of advice is to respond, “Yes, if…” whenever possible. Longstreet commented to others that he thought an assault force of 30,000 would succeed. Why did he not say: “Yes, General Lee, I feel confident we can make that assault, break the Union line, win the battle, and possibly force the enemy to sue for peace, if you give me just two more divisions.” Lee had repeatedly shown he was all in for this battle, and it seems likely he would have seriously thought about his normally cautious general asking him to be even bolder.

Finally, Longstreet does not appear to have controlled his ego. When Lee rejected his advice, Longstreet withdrew from the conversation. That Longstreet did not ask any of his colleagues to speak with Lee suggests he felt that, if he could not convince Lee, then no one could. Either way you read the situation, Longstreet’s ego got in the way.

In his magnificent “The Courageous Follower,” author Ira Chaleff contends that the most powerful tool a follower has is the ability to persuade. Our world might be a very different place had James Longstreet possessed that ability on July 3, 1863.

Steven B. Wiley is president and Jared Peatman director of curriculum for the Lincoln Leadership Institute at Gettysburg, a human capital development company that has worked with the majority of the Fortune 100 companies and scores of federal agencies. This article is based on their book, “A Transformational Journey: Leadership Lessons from Gettysburg,” which is in turn based on the leadership seminars they offer.