When was the last time you slowed down? You had no concern about time, your mind was at ease, and you were completely immersed in what you were doing. If you have a hard time remembering, you are not alone. Our minds naturally default to fast mode and automatic thinking to help us get out of bed, steer clear from danger and generally go about our day.

When was the last time you slowed down? You had no concern about time, your mind was at ease, and you were completely immersed in what you were doing. If you have a hard time remembering, you are not alone. Our minds naturally default to fast mode and automatic thinking to help us get out of bed, steer clear from danger and generally go about our day.

A fast mind relies on intuition and first impressions; it trusts that it is right and moves on. A slow mind, on the other hand, relies on deliberation and analysis; it questions and wants to learn more. This mode is how we work towards solving complex problems. We may see the world through a fast mind, but it is a slow mind that will change it for the better.

Your mind at a museum

Surprisingly, our fast minds visit museums. Studies have shown that visitors of all ages spend an average of 15 to 30 seconds in front of a work of art. A good portion of that time is spent reading the label. We get the gist, and we move on. Is that how your students approach school — hearing or seeing or trying but not thinking and absorbing?

Giving more time to an object’s label than the object itself shows a greater interest in knowing what you’re seeing than exploring the object for yourself. We likely want our first impressions to be confirmed, and perhaps learn a little bit more. But that’s all.

In both art and education, a fast mind sees. A slow mind looks, feels and questions.

How to explain what slow looking is

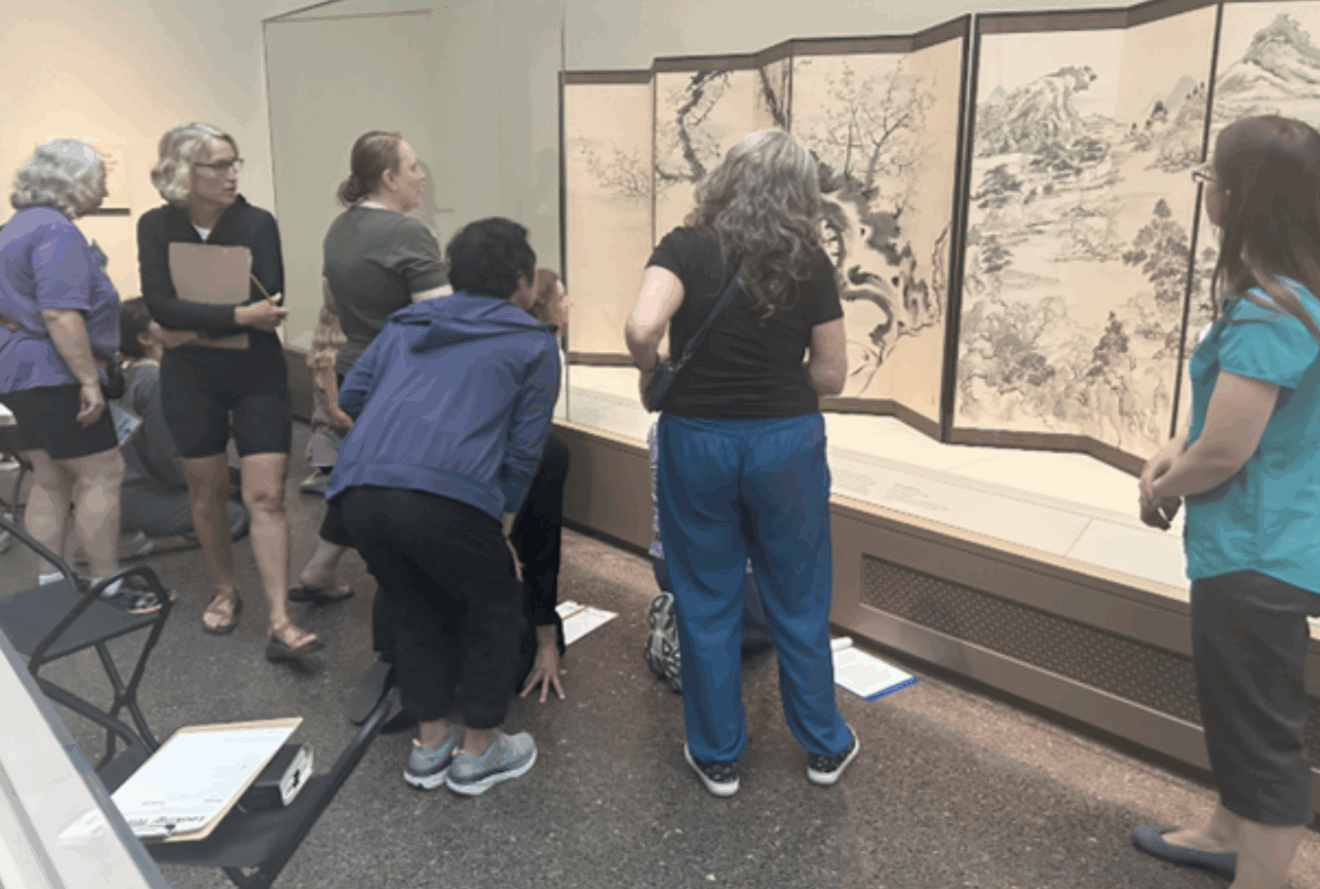

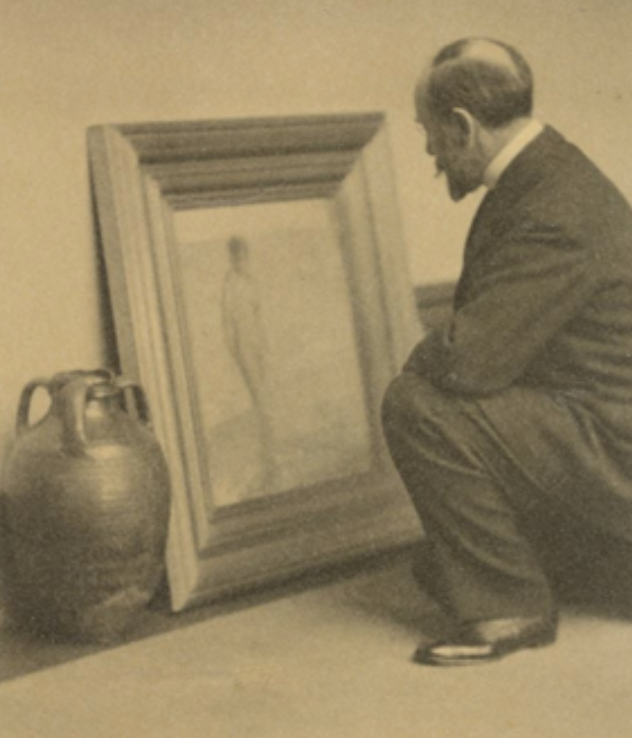

Tell your students to mentally head to an art or history museum. A slow mind intentionally takes the time to observe more than what it can see at first glance. Maybe you walk close to an object, stoop down low to look intently, then walk back to view it from afar again. That slow mind is physically taking in the object from different perspectives.

The same is true for a person on a bench sketching an artwork or artifact. They are training their eyes to capture the details. Similarly, two people deep in conversation in front of an object, gesturing and asking each other questions, are learning about each other’s feelings, opinions and personal connections.

Slow looking doesn’t come automatically. However, once you practice a few techniques to slow down, the more engaged you will become with museum objects — and even school lessons.

4 tips for slowing down, learning more

You can learn to slow down with intention at a museum through this approach:

- Intentionally choose to slow down before you get to the museum. Even if it’s the only time you’ll go there (or read a novel or work with a parallelogram), tell yourself you cannot possibly see or understand everything. The fast mind rushes through an album of an artist’s greatest hits; the slow mind deeply immerses itself in a whole album. Think of your museum visit — or that civics lesson: If you speed-read or fast-listen or quick-look, you might not remember much about what you’ve seen or heard, however exhausted you feel afterward. If you make the intention to look, not just to see, you will leave nourished and satisfied by your visit.

- Bring a notebook or sketchbook and a pencil. Think of your pencil and paper as an extension of your eyes. Let go of the idea that the drawing needs to look good, your writing needs to be profound, the grammar and spelling need to be correct or the problem’s solution needs to be done the “right way.” Instead of worrying that what you put on paper is an expression of your skills, think of sketching or writing as another way to slow down with a museum object. Make several sketches of the details you notice. Write some descriptive words or phrases to capture your reactions to a museum object.

- Move. Try examining the object from different perspectives. Walk closer (without alarming a guard!), crouch down, step farther away. Get physical.

- Delay looking at the label. Take your time with the museum object. Let your eyes wander all over it. Take in all the details, and notice which parts draw your attention the most. Once you look at the label, ask how that meshes with what you saw and felt. Jot down any new insights.

For more inspiration, try these nine guided activities you can try.

Translating slow to the classroom

Teachers can help their students slow down and work with intention.

- Lean into wait time. It’s OK to ask a question in class and be met with silence — your students’ slow minds are at work. Ignore any nervousness and harness wait time. That counteracts the desire to move conversations along quickly, get to the point and arrive at the correct answer. Insights rarely are lightning-fast. Instill a classroom culture that values taking time to think.

- Delay sharing information. Just like waiting to read the museum label, hear what your students say before you jump in. Allow time for them to make their own observations and interpretations first. You’ll be giving them time to pique their curiosity and ask questions. This skill helps instill a classroom culture that values personal discovery, where multiple interpretations are welcomed.

- Implement Project Zero thinking routines. This series of questions or procedures helps students scaffold slow looking. If you and your students are new to thinking routines, try beginner-level slow looking with activities such as Looking 10 Times Two and See, Think, Wonder. This resource developed by the Smithsonian Office of Education Technology pulls together several thinking routines that teachers have found particularly useful in helping students think about, discuss and learn from objects.

- Incorporate daily mindful breathing and movement into classroom routines. Mindfulness is being aware internally, while slow looking is about external awareness, but the two overlap and have connections. They both must be learned, and they both require concentration. When we slow down the body, we can slow down the mind, and vice versa. These mindful movement ideas may help.

You can find virtual field trips, often to museums, that will help you learn and practice these skills.

Let slowing down become part of your teaching practice — start small, be intentional and model slow looking for your students. When we take the time to truly see, we open our eyes and hearts to deeper learning, empathy and connection.

Other resources to consider

- “Creating Calm in Your Classroom: A Mindfulness-Based Movement Program for Social-Emotional Learning in Early Childhood Education” by Lisa Danahy.

- “Mindful Eye, Playful Eye: 101 Amazing Museum Activities for Discovery, Connection and Insight” by Frank Feltens, Michael Garbutt and Nico Roenpagel.

- “Ready, Set, Slow: How to Improve Your Energy, Health, and Relationships through the Power of Slow” by Lee Holden.

- “Slow Looking and Mindfulness Practices” by Reifsteck, Jennifer.

- “Slow Looking: The Art and Practice of Learning through Observation” by Shari Tishman.

Opinions expressed by SmartBrief contributors are their own.

Subscribe to SmartBrief’s FREE email newsletters to see the latest hot topics on educational leadership in ASCD and ASCDLeaders. They’re among SmartBrief’s more than 200 industry-focused newsletters.