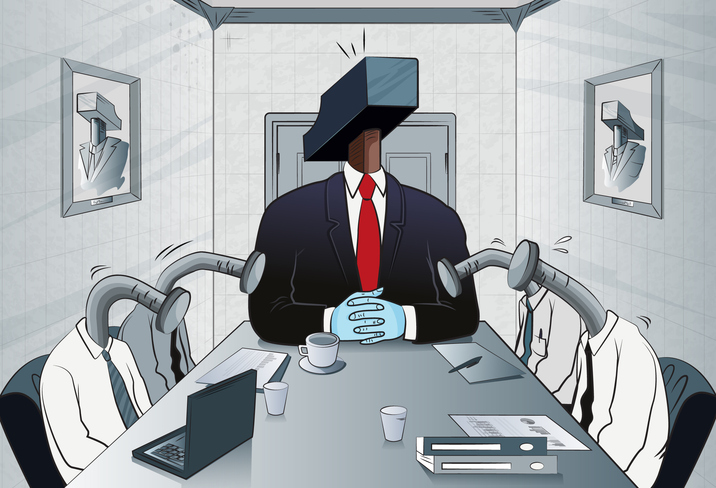

What do you think of when you imagine a narcissist? Typically, people say someone who loves themselves. Or wants other people to. Well, imagine a whole organization like that.

The idea that organizations can be narcissistic as well as individuals dates back to the 1970s. It typically involves firms requiring signs of loyalty from employees, in which they attempt to control what employees say about the firm, and in emphasizing the need for conformity and the importance of everyone being “aligned” and “on the same page.” And ever since psychologists started measuring it, the levels of organizational narcissism have been steadily rising.

The reason appears to be due to three main causes. The first is growing levels of individual narcissism, which have been rising since the early 1980s. As levels have risen in leaders, it has led them to seek higher levels of loyalty and conformity in employees. And even when they haven’t sought these things, because employees have also become more image-conscious, they may nonetheless have perceived leaders as demanding them.

The second has been the increasing levels of brand exposure and greater reputational risk created by the combination of 24-hour news, social media and cancel culture. Together, they have led firms to increasingly try to control communications, both internally and externally.

Finally, there has been an increasing focus on creating a positive and motivational environment for employees, which has led some firms to overcurate internal communications. An environment in which everyone is positive about a firm can be beneficial. But it is all too easy for it to tip over and become a culture in which people feel they can’t be open.

Understandable causes, dangerous consequences

What’s important to note here, then, is that, aside from the narcissism of individual leaders, the cause of most cases of organizational narcissism is an entirely understandable and often well-intentioned desire to either manage reputational risk or ensure a positive environment. It just went too far. Unfortunately, regardless of whether it is accidental or well-intentioned, organizational narcissism always impairs performance.

The consequences of organizational narcissism never vary. It often leads staff to pretend or put on a false front, saying what they think the boss wants to hear instead of being honest. This makes it harder for people to trust each other because they don’t feel free to speak openly. It also slows down the sharing of important information, as employees become careful about what they can or should say. Usually, good news spreads quickly, but bad news spreads more slowly, which makes it harder for organizations to make informed decisions.

In a large global manufacturing business we worked with, this became painfully evident when the CEO’s strategic transformation initiative stalled because it wasn’t sufficiently grounded in operational realities. Constant changes to it, necessitated by the facts on the ground, meant that the pace of change was continually slowed, and costs continued to mount until the CEO and the program were eventually shelved by the board. Subsequent investigation revealed that the deficiencies of the CEO’s plan had been common knowledge among most of the top three or four layers of the business. But due in large part to the firm’s can-do culture of positivity, in which people were discouraged from questioning the strategy and criticized for “being negative,” these leaders appeared to have all independently decided to let someone else be the one to risk being seen to be “disloyal” to the CEO’s plan.

Indeed, to be clear, we believe that the subtle and silent growth in organizational narcissism, which is undermining trust and information flow in businesses of all sizes and across all regions and industries, damaging leaders’ ability to ensure open communication and informed decision-making, represents one of the biggest threats to organizational performance facing firms today. It is a subtle performance limiter, and it is almost certainly already at work in your business to some extent.

Managing organizational narcissism

So, what can you do about it?

The key to combating narcissism is disagreement. Leaders and organizations must actively seek out, encourage and reward debate and questioning. There is much written on this, but as a start, try these:

- Encouraging people to share their thinking is especially critical when decisions are on the table. Unfortunately, that’s also when people feel most vulnerable and least willing to speak up. Structured tools, such as pre-mortems (imagining why a decision might fail) and red teams (challenging plans with alternative scenarios), can be helpful. There are many such methods available. You don’t need to use them for every choice — just the big ones. The goal is to make your team a decision-making engine, where their input systematically informs your calls.

- I once worked with a CEO whose trademark question was, “What do you think?” Everyone quickly learned that walking into his office meant you had to bring an opinion. He didn’t care much what the view was, but he was irritated if you had none. And it worked. The lesson: if you want people to speak up, invite them to do so. Keep asking questions. Push for perspectives as though they’re fuel, because for a leader, they are.

- Just as important is how you react when people do speak. Even if you disagree, respond constructively. That’s harder than it sounds, because sooner or later someone will say something irritating. But your reaction matters. Adam Neumann, WeWork’s former CEO, reportedly dismissed executives who urged caution as “B players” and barred them from meetings. They may or may not have been too cautious (history suggests not), but that kind of dismissal silences voices and leaves you in an echo chamber.

- Instead of asking whether internal communications make leaders appear authentic, ask whether they let employees be authentic. A negative employee can be managed. An insincere one is far more damaging. The world is rarely clear-cut, but leaders are often expected to sound certain. Each time we present things as absolute, we signal that there are right and wrong answers, which raises anxiety about “saying the wrong thing.” Better to use qualifiers. Instead of “It is like this,” say, “The most likely scenario is this.” That framing reminds people that in decision-making, absolutes are rare.

Opinions expressed by SmartBrief contributors are their own.

____________________________________

Take advantage of SmartBrief’s FREE email newsletters on leadership and business transformation, among the company’s more than 250 industry-focused newsletters.