Check out the first part of this “Simplicity Cycle” series, “How to add.”

The concept behind Garfield minus Garfield is pretty straightforward: erase the tubby orange cat from the comic strip that bears his name, but leave behind the props and other characters. The result is brilliant, fascinating, and poignant. On his site dedicated to “G-G,” Dan Walsh explains the edited comics are “a journey deep into the mind of an isolated young everyman as he fights a losing battle against loneliness and depression in a quiet American suburb.” If you have a taste for schadenfreude (and who doesn’t?), these comics can be super funny.

How does it work? Removing Garfield fundamentally changes the nature and message of each strip. It creates new space for the reader to explore, and introduces a wider variety of tones than the original comic ever displayed. For example, one G-G comic starts with a panel in which Garfield’s owner Jon says “These are troubled times.” For the remaining two panels, Jon sits and holds his coffee cup, without further comment, as if inviting the reader to join him in his thoughtful anxiety.

In a particularly dark comic, Jon says “Good night, I’ll attempt to, but fail to wake in the morning.” The final panel is completely empty, perhaps creating the impression that Jon not only died in his sleep, but predicted his own demise.

At other times the result strikes a joyful and hopeful note, as in the comic where the first panel shows a grinning Jon saying “Imagine what your life would be like if you had wings.” The following two panels are empty, granting the reader space to imagine flying like a bird.

G-G is a fascinating example of how “creation by subtracting” can work. As designers, coders, or engineers, we generally begin a design effort using additive tools, introducing new pieces, parts, and components to our creation. In fact, when we face a blank sheet of paper or an empty screen, adding is the only possible move. But as the design progresses and accumulates more parts, new design alternatives become available. Instead of being limited to additive methods (which I described in the previous 3-minute design lesson), we can eventually adopt reductive thinking models and subtractive techniques as a way to improve our design.

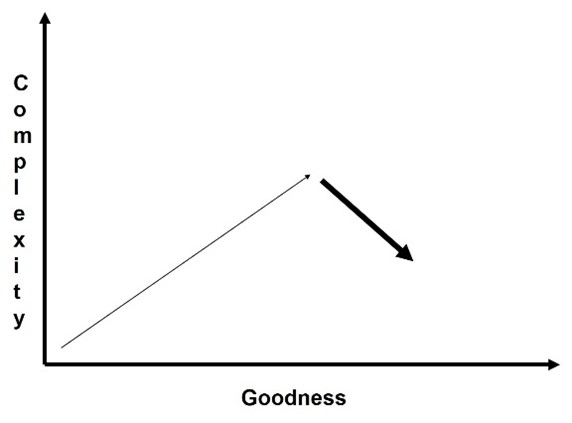

The diagram below uses the Simplicity Cycle framework to highlight a subtractive path. The thick line pointing down and to the right represents a design that is simultaneously becoming simpler and better. The slope and straightness of our specific path may vary, but if subtraction drives improvement, we’re basically heading in this direction:

Subtracting is a less obvious and less common approach to resolving a design problem than adding, so the techniques may feel unfamiliar at first. However, with a little experimentation and practice, we just might discover that taking things away is an even more powerful design approach than putting more things in. And it turns out we have several subtractive moves available to us, different approaches which allow us to improve a design by simplifying it.

Here are eight subtractive strategies to consider:

- Delete. Remove an existing piece from the design. This deletion may be a piece that is redundant, extraneous or obviously unnecessary. In other situations, we may remove a piece that appears to be useful or even essential (i.e. take Garfield out of Garfield), and we just might discover that the design performs better without it.

- Trim. Remove a portion of an existing element. This strategy is subtractive in the sense that while the component itself stays in the design, it no longer contains all its original attributes or functions (i.e. Shut up, Garfield, a site that leaves the cat but removes Garfield’s speech bubbles).

- Integrate. Combine multiple elements into a single element. Rather than two or more distinct parts, they are synthesized into a unified component.

- Shrink. Transform an existing element into a smaller version.

- Remove copy. Reduce redundancy. This strategy is useful if a design element is highly dependable and has an un-used backup, if the system’s performance is generally unaffected by the failure of a particular component which thus does not need a built-in backup, or if a replacement can be quickly introduced when a component fails.

- Trust. Remove a piece that provides a check function and trust that the remaining components will perform as designed (see No. 5).

- Polish. Reduces friction between components.

- Delay. Introduce an element later in the process than planned. This is a form of time-shifted subtraction, where the element is always intended to be part of the design but is now included later than originally planned.

Subtracting can be a profoundly creative act, and when we remove the metaphorical Garfields from our own designs, we may find we have created something entirely new and entirely better. So give it a try — grab an eraser and see what you can create.

Dan Ward is the author of “The Simplicity Cycle: A Field Guide To Making Things Better Without Making Them Worse” and “F.I.R.E.: How Fast, Inexpensive, Restrained, and Elegant Methods Ignite Innovation.” He holds three engineering degrees and served in the U.S. Air Force for over two decades researching, developing, testing, and fielding military equipment. He is the founder of Dan Ward Consulting, LLC.

If you enjoyed this article, join SmartBrief’s e-mail list for our daily e-mail on being a better leader and communicator. Each Tuesday, this newsletter highlights innovation and creativity.